By Anna Holligan

BBC News, The Hague

Bronze statues of colonial icons have been spray-painted. Black Lives Matter protests have broken out. And now the Dutch parliament has backed a petition by three teenage women requesting the addition of racism to the school curriculum.

Winds of change are swirling around the cobblestones of The Hague. Faced with a strong colonial past and a legacy of slavery, the Dutch are being asked to take a more impartial look at their history.

“We’re still a very white nation,” says Mirjam de Bruijn, an anthropologist at Leiden University. “Our colonial legacy is visible every day in our streets. There’s an inherent racism and acceptance of inequality. Racism is inside all of us.”

How the protests began

What happened in Minnesota found echoes here too. In June, more than 50,000 people knelt during demonstrations across the Netherlands.

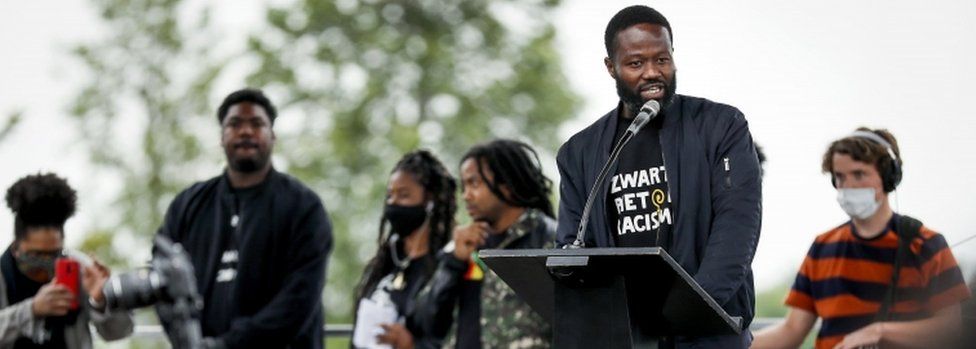

“We have deaths of people who died like George Floyd, but still no arrests,” explains poet and campaigner Jerry Afriyie, who has been detained at a number of anti-racism protests.

He points to two recent deaths in Dutch police custody.

Tomy Holten died an hour after he was arrested on 14 March, after reportedly causing a nuisance in a supermarket in the central city of Zwolle. Images appear to show one of the arresting officers pressing his foot down on his face.

In 2015, Mitch Henriquez died after being arrested for allegedly claiming he had a gun at a music festival in The Hague. An officer was given a six-month suspended sentence for applying the neck grip that killed him.

Mr Afriyie believes the Netherlands has problems with “white-supremacy” sentiment and he has his own experience: “I was put in a choke-hold and had to struggle for my life.”

Protesters complain of institutional racism and a disconnect between a society that sees itself as anti-racist and the actual experience of black people within it.

There is a distinct absence of black MPs in the current Dutch parliament. And that reflects a sense of invisibility felt by many.

“It’s a strange country,” says Mirjam de Bruijn, who finds it impossible to see the Netherlands as truly democratic when part of society is silenced or told the racism they endure is imagined.

The three teenagers fighting back

The place to get the issue addressed is in the classroom, according to high school graduates Veronika Vygon, Sohna Sumbunu and Lakiescha Tol.

The three friends launched a petition calling for lessons on racial discrimination to be added to the national curriculum.

Within weeks they had collected 60,000 signatures, and had been overwhelmed by an explosion of support from politicians, musicians and social influencers.

“In school, people told us ‘Your skin looks like poop’,” Veronika, 18, told me. “You are not born a racist, it’s taught by your parents, your environment, school. We want to unteach it, to use the same institutions reproducing stereotypes to turn them around.”

A Labour politician put forward a motion backing their petition and it was passed by MPs on 23 June, with 125 out of 150 votes.

“The response has been amazing,” says Veronika. “We are working on programmes and lesson plans to help teachers. Do I think this will make a difference and change lives for the better? One thousand per cent.”

History teacher Rodrigo van Loo believes there has already been a shift in Dutch schools. “The books mention the people who were visited by the Dutch. And on slavery, we now teach how slaves became slaves.”

He teaches in a so-called “black school”, where most pupils come from migrant backgrounds.

Bitter blackface row that divides Dutch

Every 5 December, white people in the Netherlands paint their faces black, apply red lipstick and pull on curly wigs to embody fictional festive character Black Pete.

Defenders of “Zwarte Piet” vigorously reject accusations of racism. But opponents argue that the fact it continues, when so many in the black community are upset, shows black lives matter little here.

One recent poll, however, suggests fewer than half of Dutch people now support the tradition – a dramatic fall in a matter of months.

Getty Images

Discrimination in Netherlands

Experiences of non-white citizens

- 56%in shops and businesses

- 29%experienced from police

- 40%in schools or universities

- 78%believe institutional racism exists

Source: Survey of 5,000 on Een Vandaag panel, June 2020

Old attitudes die hard, though. When veteran TV football pundit Johan Derksen suggested black rapper Akwasi looked like a photo of a man in blackface, both the Dutch men’s and women’s national teams said they would boycott the programme.

Derksen said it was a ‘”stupid joke”, but stopped short of apologising. The TV network refused to sanction him, citing freedom of expression.

Stirring up history

As elsewhere, Dutch colonial legends are now coming under scrutiny from those whose ancestors experienced the nation’s inglorious side.

During the “Golden Age” from the late 16th to late 17th Century, the Netherlands was a global pioneer in science, art and trade. Its wealth grew over 200 years through the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

But statues of famous, seafaring figures have come under attack from a group called “Helden van Nooit” (Heroes of never):

- In Amsterdam, a monument of Joannes van Heutsz, Governor General of the Dutch East Indies, was defaced

- In Rotterdam, Piet Hein, 17th-Century vice-admiral of the Dutch West India Company, had the words “killer” and “thief” scrawled on his plinth

- Outside the Dutch parliament, slogans were daubed on a statue of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a hero of independence from Spain and co-founder of the Dutch East India Company

- Riot police in the northern town of Hoorn protected a bronze statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, a 17th-Century officer who seized control of the spice trade.

A significant majority believe these monuments should stay, one survey suggests. However, a debate has stirred on the Netherlands’ history of slavery.

On 1 July, the Dutch marked the formal abolition of slavery in 1863 in the old colonies of Suriname and the Dutch Antilles.

The day is known as Keti Koti (broken chains in Surinamese), but slaves in Suriname were not freed for another 10 years, because of a mandatory transition period. Even then they received nothing, while their owners were given compensation.

Should there be an apology for slavery?

There is increasing support, but Prime Minister Mark Rutte rejected the idea in parliament, because he feared it would create further polarisation.

Statues shouldn’t be removed either, he said, as they offered a chance to reflect on a history that cannot be removed.

But D66 liberal MP Rob Jetten called for more attention to be paid to the descendants of slaves: “A large section of black people in the Netherlands say: see our pain and feel it.”

More on Europe’s debate on racism and history

https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.46.12/iframe.htmlMedia caption,

What do we do with the UK’s symbols of slavery?

- Belgium ‘wakes up’ to its bloody colonial past

- Statue of controversial writer vandalised in Milan

- Statue vandalised in row over French slavery code

- Farce over renaming of ‘racist’ Berlin station

Labour leader Lodewijk Asscher told MPs: “Being against racism is not left or right, but a sign of civilisation.”

But the populist right profoundly disagrees with an apology.

Thierry Baudet of the Forum for Democracy party laid flowers on Gen Coen’s plinth, and urged others to celebrate national heroes.

Is there a sign of change?

Apologies for slavery have come from the cities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, while King Willem Alexander apologised on a visit to Indonesia “for excessive violence” during its war of independence.

“Don’t deny the terrible wrongs we did. Amsterdam is built on the products of Indonesia,” says anthropologist Mirjam de Bruijn.

The perception that modern Dutch society is inherently inclusive and tolerant was challenged last year by the UN’s special rapporteur on racism.

“In many areas of life… the message is reinforced that to be truly or genuinely Dutch is to be white and of Western origin,” wrote E. Tendayi Achiume.

Historian Alicia Schrikker believes a failure to understand what not being white is like gets in the way of more critical reflection.

“People being raised now find it difficult to imagine what it was like,” she told me. “Going back to history is essential to understand how much of that has influenced our contemporary culture and ways of seeing or not seeing.”

If the Netherlands is to protect its open and democratic society, that may require rethinking what it means to be Dutch.

Read the original article here:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53261944